WholeLife

חיים שלמים

Jerusalem, Israel 93221

פסיכותרפיה דינמית - מאמרים באנגלית

רשימת המאמרים

1

2

![]() THE GENERAL PHILOSOPHICAL FRAMEWORK OF ROSINZWEIG`S THOUGHT

THE GENERAL PHILOSOPHICAL FRAMEWORK OF ROSINZWEIG`S THOUGHT

3

4

5

![]() THE PRIOR CONDITIONS OF THE MEETING BETWEEN MAN AND GOD Part 1

THE PRIOR CONDITIONS OF THE MEETING BETWEEN MAN AND GOD Part 1

6

![]() THE PRIOR CONDITION OF THE MEETING BETWEEN MAN AND GOD

THE PRIOR CONDITION OF THE MEETING BETWEEN MAN AND GOD

Part 2

7

![]() The Orientation of Past Time©

The Orientation of Past Time©

8

![]() The Prior Conditions of The Meeting Between Man and God © Part 1

The Prior Conditions of The Meeting Between Man and God © Part 1

9

![]() The Prior Conditions of The Meeting Between Man and God © Part 2

The Prior Conditions of The Meeting Between Man and God © Part 2

10

![]() The Prior Conditions of the Meeting Between Man and God©Part: 3

The Prior Conditions of the Meeting Between Man and God©Part: 3

11

![]() The Prior Conditions of the Meeting Between Man and God© Part: 4

The Prior Conditions of the Meeting Between Man and God© Part: 4

12

![]() The Prior Conditions of the Meeting Between Man and God © Part: 5

The Prior Conditions of the Meeting Between Man and God © Part: 5

13

![]() Description of Man's Meeting With God © Part 1

Description of Man's Meeting With God © Part 1

14

![]() Description of Man’s Meeting With God © Part 2

Description of Man’s Meeting With God © Part 2

15

![]() Description of Man's Meeting With God – Part 3

Description of Man's Meeting With God – Part 3

16

![]() On the Purpose of Man© Part 1

On the Purpose of Man© Part 1

17

![]() On the Purpose of Man© Part 2

On the Purpose of Man© Part 2

- By:

1Thes research paper concerns itself with the concept "love" as it relates to humanity according to the following criteria:

(a its source, (b its character, and finally (c the way to embgody and express it, all according to the perception of Maimonides, may his name be remembered in Righteousness and Blessing. In accordance with the dictum in the Talmud saying, "Torah learning is greater when it leads to action, "let it be His Will that this treatment of the concept will be a steppingstone to achieve love in our thought, speech and actions.

A. THE SOURCE OF LOVE

Chapters 51 and 52 of Section 3 of Maimonides` THE GUIDE TO THE PERPLEXED discuss knowing the Almighty as the source from which the love of G-d, grows. We learn that the source of love is knowing G-d, and to acheeve it one must cling to the spiritual concept that is liarned in the comment, "Didn`t I explain to you that this is the intellect that abounds in us from the Holy One; it is the attachment" which which exists between us and Him? We understand the source of love as the concentration of man`s thought in G-d, or the knowledge of G-d.

Maimonides joins the religious ideal of attaining G-d as the source of love with the philosophic ideal of a life of reflection. True, the purpose of man is reflection, but the purpose of reflection reflects the source of love, the knowledge of G-d. However the fundamental questions are asked: What is love`s explanatin, and what is the meaning of the knowledge of G-d? And how can man, in general, arrive at the source of this knowledge as a prelude to love?

Regarding these questions, it is worthwhile consedering the central chapter of the system of descriptions, THE GUIDE, Section 1, Chapter 54. There, Maimonides relies on Moses, Our Rabbi, and says that he requested two wishes from the Almighty: one, "that He should show him His strength and His truth," that is, that G-d should reveal His might before him; and two, that G-d "should describe Himself to him." On these requests G-d replied to Moses that His might is incomprehensible, and His descriptions are His acts. It is impossible, then, to know G-d from the aspect of His might, although it is possible to know Him from the aspect of His acts. The descriptions of G-d which embody Him to us are discriptions of actions. Thus, all the descriptions of which the Almighty notified Moses were descriptive of actions: merceful, gracious, forbearing. The ways in which Moses requested their knowledge and by which he was notified of them were through awareness of His acts, may His name be blesed. The Sages called these acts "attributes" naming them collectively "The Thirteen Attributes." (XXXIV:6-7)

Knowing G-d as the source of love is even called by the name "the pure thought." This is learned from the words of Maimonides in THE GUIDE, Section, Chapter 21, "That the pure thought, according to it will be love; it is the essential knowledge of G-d Himself." This direct attachment of love to knowledge teaches that the essence of the idea love did not, according to Maimonides, include the psychological eddect and the emotional experience. The source of the love of G-d is practical, thoughtful and not emotional. (See GUIDE,III:54 "`And you will love your G-d with all your heart` means with all of the strength of your heart.") Essentially, Maimonides sought to free the love of G-d from its emotional content and to turn it into a pure achievement. This approach is expressed at the end of THE GUIDE.

B. THE NATURE OF LOVE

The nature of love is purposeful. This is expressed in the fifth chapter o Maimonides` EIGHT CHAPTERS: Man must activate all the strengths of his soul to know... and will place before him at all times one purpose, and it is the attaining of G-d, may He be blessed, according to the ablility of the person to know Him. And he will offer all his acts, movements, strengths and whatever else he has to arrive at this purpose, such that none of his acts will be vain acts, meaning an act that will not lead to this purpose.

Love bears the purposeful nature of similarity to G-d and walking in His path. This assumes the form of love of attainment whose essence is attachment to the love of G-d. Maimonides set forth the decree of Jeremiah, XIX:22-3

Do not praise the wise man for his wisdom and the strong for his strengtyh and the wealthy for understanding and knowing Me that I am The Almighty who does kindness, justice and generosity on earth, in which I delighted in G-d`s address.

Jeremiah does not stop with the words "understanding and knowing Me," and this that did not suffice him for the verse to expain, is that their attacnment alone, may He be blessed, is that which venerates perfection.

The nature of love is also ethical; meaning that attainment of the knowledge of G-d is, in effect, awareness of ethical G-dly characteristics. And furthermore, the purposeful nature, which is in love, is an ethica purpose of the life of man in general. It is knowledge, the knowledge of G-d, though the purpose of this knowledge itself is ethical. Rational perfection os a characteristic of the love of man for G-d, and ethical perfection is a characteristic of the love of G-d for man.

Also, we discover an entirely new picture of Maimonides` thought on man and the nature of man`s love of G-d: Man does not trek towards the love of G-d in a straight line, but in a circular line. The way is that of ethics and knowing G-d, though the path does not end at this point. It returns and is overturned: From knowing G-d there develops a return to the ethical attributes, and the ethical nature of the love of G-d is in the awareness of the G-dly attributed. This means that attaining G-d is essentially attaining His works. Maimonides continues, (GUIDE,III:24) "It is not appropriate to praise only for the attainment of the knowlidge of His ways and His descriptions." His acts being synonymous with His descriptions, we may therefore deduce that we must seek to know His acts in order to perform them. Again, the intention is to replicate the thirteen attributes in order that we may walk in their ways.

But, how is it possible that man will walk in the path of The Almighty? That is, how can man replicate G-d and imitate His deeds? How can we understand this characteristic of love, which is the very fruit of love? To resolve these questions, we must fundamentally distinguish between act and effect. In man, the act results from the spiritual effect, from some creation or quality within the soul, whereas the acts of G-d do not result from a spiritual characteristic or from any essence.

Maimonides stresses this in his discourse on the descriptions of the acts in general saying, (GUIDE, I: 54) "This matter is not one of attributes, but of deeds similar to the acts which come to us from the attributes." That is, the acts of G-d are similar to ours, but there is no comparison in the causes inducing the actions. The acts of G-d do not result from any effect or spiritual characteristic, but they are as if they result from effects. The appellations "graciousness" and "mercy" and "slow to anger" are not understook as G-d loves or pities (or even hates). The understanding is only that the acts resulting from G-d result as if from love, mercy or hate. Now the term replication is understood: This characteristic of love os the walking in the path of G-d, the imitation of His acts. There os no replication from the aspect of effects or spiritual charactersitics. The replication is not in the spiritual realm, but in deeds.

To summarize, the nature of love is intellectual rationalism, an act approaching truth, which is knowledge of G-d; the nature of love is purposedul and reflective, knowing G-d so that we may walk in His ways; and at a certain level, love bears an ethical character.

C. THE WAY TO EMBODY AND EXPRESS LOVE

Theapex of process-reflective devotion is nothing other than reflective exertion toward the awareness o G-d. Reflective awareness is a processs of absorbing a reflective abundance from G-d by means of the active intelligence. This turns the human intelligence into a bridge between G-d and man. This bridge is dependent on man alone, in his intelligence and in his concentration of his thought upon The Almighty. Therefore, in the strengthening of his intellect, man will come to the love of G-d.

This reflection, however, is not only the theoretical, philosophical intelligence; it is also bound to the internal emotion of man. Intelligence, according to Maimonides, (GUIDE,III:51) is not only rationalistic speculation; it includes the sphere of feelings and emotions.

At a certain plateau love no longer remains in anything other than the beloved, and this is termed by Maimonides (Ibid) with the appellation "desire." This love is already planted in the material of the desire in a way that perfects it, leading us to conclude that the true belief is the religion of love.

Man has a purpose, and it is the attainment of G-d. Man will attain G-d through his entire deeds. Moral and ethical conducts serve as a preparation and as a means for this purpose. Man will not arrive at the supreme purpose if he will not control his morality. If he will not restrain his desires, if he will not internally discipline himself, if he will not improve his understanding and will not strengthen his will, he will not arrive at the supreme ethical stratum.

In the YAD HAHAZAKAH, Maimonides explains, "The revered and fearful G-d commands to love and fear Him, as it is written, `and love your G-d, ` and it is also writtten, `The Lord your G-d you will fear. `" How is it possible to both love and fear Him? It is possible at the time when man will observe His acts and His marvelous creations and see in them His wisdom, which has no measure and no end. Maimonides states further, in the MISHNEA TORAH, (Book I, p.36) "The servant from love studies Torah and follows the Commandments and walks in the ways of the wise not cecause of something in the world, and not because he will otherwise see evil, and not in order to inherit good; but he does the truth because it is truth and resultantly ends favorably..." Then, man will love G-d with a great love, overflowing and mighty, such that his soul will be linked to the love of G-d, G-d as a unity, with all his deeds in the name of Heaven for the sake of the attainment of G-d and performance of the Commandments for their sake alone.

CONCLUSION

According to current and classical thought thought, love is an essential need of each and every indinidual, although the nature and purpose of love is sometimes misconstrued. The essential love is the love of G-d, and the way to achiece it is through the intellect. The ultimate effect o this process is the attainment of G-d and the doing of His Commandments. In closing, we cite the "blessing of love" (Recited in the morning prayer service before the SHMA) which, in for man and man`s love for G-d.

LOVE OF THE WORLD, OUR LOVE, OUR LORD, OUR G-D, YOU HAVE BESTOWED EXCEEDINGLY ABUNDANT COMPASSION ON US. OUR FATHER, OUR KING, IN YOUR GREAT NAME AND FOR THE SAKE OF OUR FATHERS WHO TRUSTED IN YOU, WHO TAUGHT THEM THE LAWS OF LIFE TO DO YOUR WILL WHOLEHEARTEDLY, THUS WILL YOU FAVOR AND TEACH US. OUR FATHER, THE MERCIFUL FATHER, HAVE COMPASSION ON US AND PLACE IN OUR HEARTS UNDERSTANDING, TO KNOW AND TO REASON, TO HEAR, TO LEARN AND TO TEACH, TO RUARD AND TO PERFORM, AND TO DO ALL WHICH YOUR TORAH TEACHES US WITH LOVE. ILLUMINATE OUR EYES WITH YOUR LAW, AND ATTACH OUR HEARTS UNTO YOUR COMMANDMENTS. UNITE OUR HEARTS TO LOVE AND TO FEAR YOUR NAME S THAT WE SHALL NEITHER SHAME NOR REPROACH NOR WAVER, FOREVER. FOR IN YOUR HOLY, FRAND, MIGHTY AND REVERED NAME, WE TRUSTED. WE SHALL REFOICE AND FEAST IN YOUR SALVATION. IN YOUR MERCY, G-D, OUR FATHER, AND YOUR MANY KINDNESSES, SO NOT ABANDON US EVER. BRING US SPEEDILY BLESSING AND PEACE...FOR YOU ACT WITH SALVATION AND CHOSE US FROM AMONG ALL PEOPLES, AND BROUGHT US TOGETHER, OUR KING, TO YOUR GREAT NAME, ALWAYS INTRUTH WITH LOVE, TO THANK YOU AND TO PROFESS YOUR UNITY WITH LOVE, AND TO LOVE YOUR NAME. BLESSED BE THOU.OUR LORD, WHO CHOOSES HIS PEOPLE ISRAEL WITH LOVE.

* המאמר מבוסס על סמינר בנושא: ,Medieval Jewish Philosophy שבו השתתף המחבר במסגרת לימודי הדוקטור בפילוסופיה אקזיסטנציאליסטית, בשנת 1992 ב- Columbia University NY. עבודת הדוקטור של המחבר חקרה את הגותו של פרנץ רוזנצווייג, שספרו ניצחון החיים את המוות שיצא לאור בשנת 1994, מבוסס על פרי מחקרו.

THE GENERAL PHILOSOPHICAL FRAMEWORK OF ROSINZWEIG`S THOUGHT

By:

2The author describes the religious, existential philosophy of Rosenzweig in the context of this historical background and its place I "The New Thinking”, the philosophy which followed Hegel and linked man to experiential reality rather than enclosing him in the world of concepts.

The latter vision of man was Hegel’s synthesis of 2000 years of thought. Rosinweed utilized Hegel’s systematic method but searched for a philosophy of the real world to replace Hegel’s "worldly spirit”. Blending intellect and revelation, Rosenzweig`s man is free and responsible when God, man and the world meet.

Mea`s freedom however, is limited. Lacking knowledge and purpose and fearing death, man must also think of God, and in that act is able to observe and indeed, create reality in the present. The love of God conquers death and liberates man from the "you" in favor of the "we". Man has purpose.

The unique framework of Franz Rosenzweig

The philosophy of Franz Rosenzweig is one of the most interesting and surprising innovations of modern thought, both general and Jewish. There exists a bacground of distinguished modern Jewish philosophers from Moses Mendelssohn, the first philosopher of modem thought who systematically defined the essence of Judaism, to Hermann Cohen and Martin Buber. However, Rosenzweig was the first to inject existential philosophy into Jewish thought and give it direction, both theologically Jewish and original.

Rosenzweig coined a terminological system whose terms were taken from Jewish usage. He provided its own guidelines and created a unique philosophical weave containing an interpretation of the struggle of Judaism with the other monotheistic religions.

Rosenzweig emphasizes a unique and orderly conception of life. In his epistle "On Education," he wrote: "The Judaism to which I refer is not `literary` and is not grasped by the writing or reading of books. Even - forgive me all modern thinkers - it is not to be `experienced` or `cultivated`. One may only live it. And not even this – one is simply a Jew, and nothing more" (his Life 159).The Star of Redemption, Rosenzweig`s masterpiece, is written in a remarkable, ordered, dialectical singularity. In The Star of Redemption, Rosenzweig made one of the few attempts to formulate methodically religious existential philosophy (MiMytos 262-273), This attempt makes the book unconventional, an exceptional work among the philosophical works of our time.

Rpsemzweog. Cpmtrary tp the great classical philosopher, stresses the lack of identity between thought and reality. Instead, the book is based on three elements - God, the world and man - which preface all logical action and may be conceived only by means of faith The Star of Redemption also strays from the accepted line in the existential philosophy of Kierkegaard and Sarte, in that Rosenzweig attempts to prepare a philosophical method par excellence.

Rosenzweig`s life and personality also uniquely reflect his philosophy of life: "Man thinks that he philosophizes, but in actuality he writes his autobiography ("From Revelation" 162). Although raised in an assimilated environment, educated at the knees of the classical German idealism and philosophy of the Enlightenment so distant from that of religious belief, he suddenly tumed sharply to faith. Author of the philosophical treatise Hegel and the State, Rosinzweig subsequently became the author of the theological book The Star of Redemption and translator of Hebrew poetry of th Middle Ages and the Beble to German. He Stood at the threshold of converting to Christianity and retured to Judaism to cecome one of its most profound thinkers. Intellectually acute, probing and exhilaratin, his essays frequently contained irony and humor though written furing the last eight years of his life while he was critically ifl and in agony, paralyzed throughout his body and unable to speak (His Life).

Notwithstandig the uniqueness of the man and his method, Rosenzweig`s philosophy is a not a singular phenomenon, but is a total spiritual process which characterizes post-Hegelian philosophy. This process places in the center of thought not understanding or an abstract method but rather existential man, real, vital man ,with all his existential problems, emotion and agonies of soul.

The philosophic path leading to Hegel

In the approximately two hundred years which preceded Hegel, a direction in philosophical thought had commenced and developed which led inexorably t Hegelian thought. Among the significant philosophers of this developmental period was Francis Bacon (1561-1626), the father of English empiricism, who maintained that the source of undersanding o knowledge is the experience we acquire by means of our senses. Bacon developed the scientific method, which was adopted and adapted by, among others, political philosophirs defferent one from the other as Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679) and John Locke (1632-1701).

Man`s dependence on his perception developed from a scientificmethod to a philosophical concept. George Berkeley (1685-1753) set forth the rule: "to be" is to "be perceived" in the mind of man. He further asserted that the one thing which exists for certain is Spirirual reality, thought, the result at which the senses arrive. The skepticism of Berkeley was buttressed by David Hume (1711-1771), who denied the possibility to understand via our intellect any truth of reality. Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) neither accepted the skepticism of Hume nor the earlier empiricism, and he suggested a synthesis which transferred the center of gravity from the obfect to the "I." We lmpw. C;ao,ed Kant. By means of our senses as shaped by our ntellect and not by the world surrounding us.

Kant was not the only philosopher who nourished the "I". René Descartes (1596-1650) based consciousness on one fundamental element "Cogito ergo Sum." Gottfried Wilhelm Leibnitz`s (1646-1716) theory of monadology strengthened the "I" of Descartes, and the monism and natural determinism of Baruch Spinoza (1632-1677) found in the "I" total unity of spirit and the entirely natural.

Thus, the broad spectrum of philosophical doctrines in the approximately two hundred years which preceded Hegel Began to emphasize deliberation on man's place in the world. Following Hegel, there occurred significant and distinctive movement in philosophical thought, one which properly, as described by Rosinzweig, could be called "the new thinking."

The immense significance of "the new thinking" will become apparent following a brief review of the theories and teachings of Hegel.

Hegelian theory and reaction to it as background to "The New Thinking"

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770-1831) contributed to philosophy in the two following ways:

1. He established the history of philosophy as a central authority and integral part of philosophical education. The dialectic observes things in motion, flowing, and knows that not everything, which was true yesterday, will be true also tomorrow. By its nature, the dialectic is likely to accustom man to greater tolerance.

2. He made the initial determination that the previous various philosophical methods are expressed in terms of the development of cognition towards one idealistic philosophy, which strives towards an absolute and exclusive truth, that is, to the "worldly spirit" – the divine orientation which aspires to bring the human world to complete fulfillment of spiritual freedom. Hegel saw in the history of philosophy a steady march towards "absolute knowledge". Philosophy was not only a matter of understanding history but rather was the force and the best means to direct the course of history ("die absalute Macht" ), to make the cognitive path bring about events. However, the striving of Hegel towards one total and complete philosophy, the one philosophy, which strived for absolute truth, conflicted with the many philosophical doctrines of earlier philosophers.

Hegel solved this conflict with his dialectic. Philosophical conceptions based on theses, that is, On assumptions of only partial perception of verity of the concept. Become in the course of thought anti-theses. These anti-theses are also partial in their perception of the verity of the concept, however their fusion engenders mutual completion, synthesis, realization of one philosophical truth ("die Tatalitӓt"). In other words, one must recognize any philosophy only via its conflict with other philosophies, but one must recognize also its veritable elements.

Philosophy absorbs within it the fruits of the spirit of the earlier period, which opposes it, and that spirit completes and improves it and creates the Hegelian synthesis.

"That philosophy which is the last chronologically embodies the result of all the previous philosophies, and therefore it must contain the principles of all of them; thus, as philosophy, it is the most advanced, fertile and explicit" (Enzyklopӓdie, sec, 13, 47).Each philosopher, then, represents a specific stage of partial truth on the way to the entirety.

A similar idea was recently proposed by Natan Rotenstreich, born in 1914, approximately 150 years after Hegel ( Al Hakiyum 25-28). According to Rotenstreich, every person must feel himself a necessary link in the development of custom, which is the complex of connections, which are transferred in each and every generation. The consciousness senses that one is a participant in an enterprise of giants that will never be completed. The I-myself is turned, then, by one's modest original contribution to a part of some infinite thing. Man is not the initiator of processes; he knows that the world does not begin with him. Similarly, he cannot put a to the enterprise with which he is associated, and he is, therefore, a part of it forever. Rotenstreich emphasizes the personal, subjective element, but there is no moment of philosophy perfecting itself, as there is according to Hegel.

Rosenzeig utilized the systematic and methodical concept of Hegel, perceiving him as "the great inheritor of two thousand years of the history o philosophy" (Star 61), but did not conclude therefore that Hegel was the sole possessor of philosophical truth or that his predecessors propounded false conceptions. Hegel's dialectic resolution was not a conclusion after which no advancement of thought, which opposes the essence of his dialectic vision, could be drawn. Philosophical weaponry of a fresh and innovative type was necessary to resolve philosophical problems as they continued to arise.

This yearning for a new type of philosophical thinking that will function in the real world perceived the existence of man as he is rather than in terms of Hegel's "worldly spirit." This longing was expressed, for example, in Nietzsche's "changing the scale of all values" and in the materialistic philosophical thought of Karl Marx (1818-1883) and Ludwig Andreas Feuerbach (1804-1872).

Not only was Hegel's metaphysics being critically analyzed, his "philosophy of nature" also was revealed as being false. His attempts to perceive the phenomena of nature from abstract assumptions and not from experimental science was mocked by expert researchers such as Carl Friedrich Gauss in his research on geometry and Hermann Ludwig Ferdinand von Helmholtz in his work on the consciousness (Lectures).

Hegel observed the world from the aspect of the absolute spirit, the "perfect" consciousness of abstract thought and did not consider the existence of real man as he is, living in the concrete world of his direct experiences and his real problems. Hegel perceived the world as consolidated and united, as an infinite ideal, forever unattainable by science, a world which does not bring man to concrete actuality at the depths of his soul.

Hegel enclosed man in a world of abstract concepts, seeing man as a world in miniature, which loses its connection with the true and vital reality and is forever incapable of finding it. Man became, instead, a part of the method, a part of a speculative, magical, worldly system - the world and man are "one flesh" - united and linked one with the other. Consciousness does not bring one to true and real cognition, rather it results from the elemental and specific experience, maintained Hegel's opponents.

Contrary to Hegel's opinion, Hegelian thought was not complete. Bacon, who two hundred years earlier distrusted thought in and of itself and favored knowledge based on phenomena of nature and experiment, and Hans Vaihinger, who asserted two generations after Hegel that thought is unable to recognize the "absolute truth, " were only two of many philosophers who disputed Hegel's claim. There were also other doctrines, which were inconsistent with Hegelians thought. Among these doctrines are phenomenology, founded by Edmund Husserl (1859-1938), which currently dominates in Germany and France. Phenomenology seeks to light the true position of man's consciousness by spiritual or external data ("phenomena") without any ontological- a priori determination.

Another dissident vis -á - visa Hegelian thought is Hermann Cohen (1842-1918), considered one of the fathers of the neo -Kantian "Marburg School." Cohen asserts that the "logic of the inception" ("Logik des Ursprungs") or transcendental ontology seeks the "true reality" or the final essence in thought, meaning that examination of the spiritual a priori creation, exposure of the data from the beginning as an infinite process, is that which determines the programmatic status of the consciousness of man. Cohen seeks to realize society organized on the principles of ethics and the safeguarding of man's honor.

The philosophers who followed Hegel were dissatisfied with idealistic philosophy; they did not agree with Hegel that consciousness does not bring one to true and real cognition and began to develop philosophic thought that would not be restricted to the abstract and traditional method of Hegel. They sought, furthermore, to use philosophy to find resolutions to the problems bothering real people in the concrete world.

"The essential tendency of philosophic activity must bring the philosopher to man ...the special symbol of recognition of man turns his independent essence to a unique personality which exists for itself..." (Principles of the Philosophy 60). In his book The Essence of Christianity ( Das Wesen Der Christentums), Feuerbach maintains that the existential reality in the life of man is in his belief in human nature and in good deeds in this world. Marxian and Nietzschian thought similarly conflicted with that of Hegel on the essential point set forth by Feuerbach.

The difference, then, between Hegel and those who opposed his thought is in the view of the relationship of the man-philosopher and philosophy, Hegel considered each philosopher as an instrument of philosophy, a representative of partial truth at a certain stage of the development of philosophy, That idea about which the philosopher thinks becomes an idea, external to the philosopher, abstract and "perfect, " on which the philosopher speculates and is not a part of him.

Form the perspective of his opponents, not only was there a new concept of philosophy; there was also a new brand of philosopher. Man is now the determining factor; he is no longer enclosed in a world of concepts, but is tied to vital. Concrete and direct, experiential reality. Man has, in the words of Rosenzweig, a "world view," he "takes a position " (Star 143). He is not an instrument of philosophy; rather philosophy is an instrument of the philosopher, of man. "The philosopher lowers himself humbly to his experimental. Existing "I," and then his doctrine will be more veritable, concrete and closer to the truth" (Dialogical Philosophy 173).

Another conflict with Hegelian thought was led by the non-rationalists, those philosophers who opposed a philosophy in which man acts according to the intellect alone, leaving no place for the demands of the heart and feeling. Søren Kierdegaard (1813-1855) claimed, for example, that Hegel changed religion to an absolute, conceptual-cognitive idealistic philosophy, which prevents man from attaining the possibility of direct connection with God. He declared that "truth is subjective and that the principal element in philosophy is `the subjective philosopher`" (post-Scriptum, sec. 2).

Hegelian thought monistic idealism, which solves everything by one principle, the idea the "spirit" - prevented man from making the connection of faith. The world is, Hegel claimed, only an idea of God without a theistic undertone; rather, it is pantheistic, since things are not created by the idea: they are the idea itself. Nature, science and the arts are all accomplishments of consciousness individual man also is the fulfillment of consciousness, and there is only the conscious, so the private "I" has no place in this method. The "I" is similar, as in the theory of Spinoza, to a "light wave rolling along the waves of the ocean." The object ("substantia") according to Spinoza is the spirit according to Hegel, each engulfing everything within it. Thus, the solitary "I" cannot face God, as one who stands before God whether in prayer or as sinner or as a thinker.

The basic assumption of belief is that man can stand and present his essence before God, that God can speak with him and he can speak with God, or in the words of the German historian, Leopold von Ranke (1795-1886): "Here every age is really immediate to God" (Star 225). Ranke depicts the events of the past "as they were when they occurred." That is, the events are depicted b means of the revelation of God in the metaphysical ideal image, which gave significance to the occurrences, and not by means of the intellect ("The Significance").

In refuting Hegel, the non-rationalist Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph von Schelling (1775-1854) claimed that in rationalistic systems we can attain only knowledge of the possible and general laws knowledge of the real is always individualistic, it requires an act of the will which results from a personal need which can not be supplied by possibilities or general laws. Against the "negative" rationalistic philosophy Schelling placed a "positive philosophy," based on faith and will, which philosophy created the powerful and innovative basis for existential, religious philosophy, from which philosophy Franz Rosenzweig was influenced greatly.

Arthur Schopenhauer (1788-1860) and Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) raised the "will" above "consciousness" ("ratio") (The World). Schopenhauer claimed that the will resembles a thing which itself is outside our ken, beyond the ability of our consciousness to understand; the will is the singular reality in us and in the entire world. Man's consciousness serves the power of blind will, which lacks purpose and proof and will never be satisfied (compare Star 47, 49 and 57). Nietzsche holds that only the will to govern and be powerful exists in all beings. Will is the active element in natural and human phenomena; our mental consciousness distorts and opposes life, and science is of value but is not veritable.

Among other non-rationalists who contested Hegel's monastic idealism were Theodor Lessing (1872-1933) and Solomon Ludwig Steinheim (1789-1866). Lessing argued that truth is not revealed by consciousness, that it is hidden from consciousness and found among the silent forces, which activate and direct the consciousness in its action (Einmal). Steinheim (1789-1866) asserted that one does not reach religious truth (creation of the world, revelation) by mental deliberation since this truth is subject to revelation only. He "denies speculative philosophy because of its rationalistic nature and makes faith itself a type of consciousness, not identifying it with the rationalistic consciousness" (Al Hakiyum2: 168).

Philosophy`s two separate paths

Rosenzweig`s thought has a special place among the thinking which disputed Hegel. Althogh he belongs to the non-rationalist stream of thought, continuing the line of Schelling, Kierkegaard, Schopenhauer and Nietzche, Rosenzweig relies heavily on the anthropological motifs of Feuerbach which are "the first revelation of renewal of thought" (Naharayim 232). However, there is also an interlacing of rationalism and anti-rationalism, as is evidenced by the following:

"Revelation remembers back to its past, while at the same time remaining of the present; it recognizes its past as part of a world passed by...for in the world of things it recognizes the substantive ground of its belief in the immovable factuality of a historical event" (Star 215). "There is something in consciousness which is beyond consciousness...consciousness is the basis for reality, but consciousness in its very essence is also reality" (Naharayim 207).

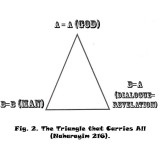

Thus, Rosenzweig`s philosophy follows two paths: One road philosophical theology chose for itself, in which the intellect is the nourishing factor. The philosophy of religion trekked the second path, revelation serving as its basis. These two paths, according to Rosenzweig, complement each other, one nourishing the other, and neither can exist independently. This conception is comparable to Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274), who also created a great synthesis between science or limited consciousness and the perfection of belief.

However, while Aquinas derived belief from Christian revelation (Basic Writings), Rosenzweig derived it from the soul of man, according to which the relationship between philosophy and theology is determined. Rosenzweig, contrary to Steinheim, noted that he was assisted by intellectual, philosophical means to prove its substance. Rosenzweig opposed forcefully any existence-belief doctrine, which is itself based on his conscious investigations. His anti-rationalist doctrine resulted from faith, but this faith was drawn from the rationalistic history of creation (Star 213), and in this aspect, his doctrine is not different from others constructed on logical, rationalistic concepts.

Rosenzweig opposed Hegel zealously. Instead of the dated abstract thought of Hegel came concrete "new thinking" connected to words, men and real experiences.

Man is free - he is own master

The act of transferring the center of gravity from philosophy to the philosopher created not only a responsibility for man, but also emphasized that man is free. He is his own master; the entire responsibility for his existence rests on his shoulders alone. Man inhales his freedom from the will and imagination. He does not breathe freedom from the advancement and attainments of science as propounded by materialism, nor does he find it I the creative spirit of man as propounded by idealism nor from intellectual knowledge of the world pursuant to rationalism. Nietzsche, for example, perceived a new form through whose strength of will exposes the subjective values which condition thought and human conduct on the freedom of his choice.

Rosenzweig proclaims a "very personal type, a type of philosopher of world view, one who takes a position" (Star 143), who rises and flourishes on the pedestals of freedom, responsibility and ability at the time of the meeting of man, God and the world and, in regard to a Jew, during his struggle with the Jewish way of life of practical commandments.

The philosophic "I" of Kierkegaard and Rosenzweig is not the solitary "I" of Immanuel Kant, an "I" which knows nothing about the world, with which it has no contact. Similarly, Descartes, in stating "Cogito ergo Sum" did not speak of his private "I" but of the abstract thinking "I". Yet Kant speaks incessantly about the "I." Which is the center of a methodical system, but as Kierkegaard says, insofar as one speaks persistently about the "I," that "I" becomes thinner and thinner until it becomes ultimately the actual spirit of the dead (Dialogical Philosophy 17).

According to "the new thinking," freedom of choice is not a matter of obligation or compulsion which comes to man from without by command or decree. This freedom is man himself - existence - "existence for itself" ("Fürsichselbstsein"), according to the German philosopher, Karl Jaspers (1883-1969) or "being itself" ("sich zu eigenist") in the words of Martin Heidegger. Therefore, he cannot flee from himself except by suicide and death.

Man has no choice but to be free. Thus, in every circumstance we are responsible, since responsibility rises from the ground of freedom (L`Existentialisme 64). One errs if he thinks he can pack and flee from himself via the Kantian Or Hegelian abstract dogma. Thus, man has two available courses: the way of favoring freedom and the way of opposing it. Life for the sake of freedom is true life, authentic life. One who utilizes freedom in order to fight it or to limit its domain in the world lives an insubstantial, inauthentic life. Such a life is not consistent with the nature of man (Portrait 75).

Man is free to create good and evil, truth and falsehood. He approves or negates the world and proclaims his presence and nothingness. Man who chose freedom chose well, and not only for himself but for all humanity (L`Etre 143). The individual is the source of freedom. There is no freedom other than the freedom of the individual. For this reason, each man must create and develop the truth of the test of the values as well as the values themselves. In respect of our lives and experiences, there is no world other than the world of man. Even values are nothing other than values as they relate to individual man. Thus, the individual must create values. Without the individual, they would not have arisen and there would be no values (L`Existentialisme 34-35). Man by nature is neither good nor evil. He is good or evil to the extent that he increases freedom in the world.

Freedom, then, is neither a priori nor objective. It is the being of man who lives it every day and every moment. It is the true existence since it exists for itself (L`Etre 641).

On the difficulties which gave birth to existentialism

Rosenzweig sought refuge from extreme subjectivism when he abandoned in 1913 the idealistic philosophy and the historicism of Friedrich Meinecke (1862-1954), his teacher (see Die Entstehung). He returned to theology, to the non-rational faith philosophy, while deliberating on "the clear brightness" (Star 143) of subjectivism, which Heidegger rooted in his creation of pure subjectivist philosophy.

Rosenzweig`s explanation indicates the lack of clarity that existed in the world of philosophy. Each philosopher, religious or not, aspired frankly to nullify the being of man as object, desiring to see man as subject only. However, in perceiving the "I" as subject alone and turning their back on the objective element in their philosophical thinking, these philosophers exposed themselves to significant difficulties. Nikolai Aleksandrovich Berdiaev (1874-1948) spoke of the decline of freedom, of freedoms lack of candor and man's subordination to freedom. Jaspers saw in subjectivism a prison, comparable to the snail who builds its house and is forever tied to it. It is not surprising that in this attempt the real freedom withdrew upon the presentation of an imaginary freedom.

The freedom represented is abstract, a vague freedom. Indeed, there is no true freedom of choice since our options are always limited a d dependent on factors upon which we have no, or inconsequential, control. Man did not pray for simple, corporeal or metaphysical freedom. He wanted real freedom in thought, economics, religion and throughout his personal life. Man wanted freedom to lift stumbling blocks from the path of life, control disease and catastrophes, master the environment and improve generally that which exists. Such a freedom is expressed in action innovation, creation, and revelation of the clandestine and knowledge o the hidden. Existential freedom is not turned toward the external world of the real and vital meeting with God and the world; instead, it is turned to the abstract, to the intangible.

Freedom of choice, then, is minuscule. According to existentialist thinking, we are not free and independent people, but rather each of us is made gradually "a man of the multitude," one among many, one who lives by the doctrine of "sit and do not act.":

1. The lack of knowledge.

We live our life without understanding it, without knowing anything about our purpose and what we must do. Even if man has a conscious nature, he cannot conceive reality. As a result, he cannot be at home in the world, and he is "thrown" into an adversarial environment. This alienation is apparent in Sartre's novels and plays, the dramatis personae being uprooted from their societal environment and removed from their past, each lacking internal spiritual unity. What determines the character of the confrontation of man with his world is not the intellect; instead it is a certain essence, which is described as nausea or anguish at the finality and fragmentation of human existence.

In respect of life and death, existence is nothing other than passing from nothing to nothing. Being, in its generality, is not understandable and cannot be known since it is connected, on the one hand, to human consciousness and, on the other, it is given to us forever fragmented so that man perceives always his limitations, the fragmentation of his being and consciousness. Franz Kafka (1883-1924) stresses that without knowledge, minuscule man is lost I the modern world, which is arranged with no way out. There is no other possible way for the hero of The Trial (Der Prozeβ ) other than to accept the judgment of death, though he does not know for what, why nor by whom he is accused, tried and sentenced.

Modern society is mysterious, a sort of blind and evil force which prevents the individual from exercising free choice and the joy of life, permitting him only to yield to his uncomprehended fate. Without knowledge, one can not know the expected, and the lack of this knowledge leads to fear of the unknown, and this fear leads to uncertainty, confusion and helplessness.

2. The fear of death.

Martin Heidegger, the extreme and heartless realist, presents an authentic being, founded o the possibility of a race toward (the fear of) death. One must live, Heidegger claims, though the sole reason for his life is his death. From the moment one enters the world, we accept the sentence of death. One has no choice in this matter. If so, how can man function with this ever-present active and tragic obsession? For fear is a strong emotional reaction with physiological consequences such as paleness, trembling, accelerated pulse and breathing and dryness of mouth which can ultimately result in the cessation of all hope and total paralysis of creation caused by the entire waste of one's energy.

3. The lack of purpose.

Existentialism will never perceive purpose in man since man is not yet defined inexorably. The objective of a priori good disappeared since there is not now any compete and infinite consciousness that will calculate it. Fyodor Dostoyevsky (1821-1881) wrote: "If God does not exist, then everything is permitted" (The Brothers Karamazov). Sartre and Nietzsche ignored the existence of God, and Heidegger stated that all existence is man and nothing more. Man abandons the world of values and the a priori commandments, which can justify his behavior because he is unable to find something to rest upon his world has no purpose and therefore also no ethical values.

Such is the dismal condition of man. He is comparable to one who walks on a tightrope above the abyss whose bottom disappears from sight. Is there no exit from this fearful vision?

The conception of religious existentialists as a clear expression of "the New Thinking"

The religious existentialists asserted that since existence is a tragedy and there is nothing on earth that can free man from the feeling of trepidation, man is likely to conclude that he must thing also of Good. Man is not acquainted with God and does not know if God will accept his entreaty, but man must take the leap toward the concealed, toward God. This daring leap contains the belief and hope that God exists, that he is compassionate and that God can help.

The religious philosophers, Berdiaev, Karl Barth, Buber, Kafka, Kierkegaard, Schleiermacher, Jaspers, Marcel and Rosenzweig, chose a solution of fear and dread, which fear is based on the failure of the intellect to attain belief. The intellect rises up against belief.

Religious man is forever immersed in the fear that perhaps the intellect will predominate and the faith in God will be lost. He must exit the boundaries of the intellect and jump into the sea of faith. Belief is the greatest and most difficult thing it commences at the place that thought ceased to act. The imaginary freedom of Sartre is infinite, likening man to God and causing the "heavy burden man must bear" in the words of Kierkegaard. The religious philosophers exchanged and imaginary freedom for belief; they considered belief the true freedom.

In respect of belief, the religious philosophers determined the following:

1. Knowlidge is a requisite and decisive factor.

For example, Rosenzweig "recognizes the substantive ground of its belief in the immovable factuality of a historical event" (Star 215). Rosenzweig considers the facts of leaving Egypt and the occurrence of the events on Mount Sinai as facts, which comprise the source from which we know the creator.

"Or hath God assayed to go and take him a nation from the midst of another nation, by temptations, by signs, and by wonders, and by war, and by a mighty hand, and by a stretched out arm, and by great terrors , according to all that the Lord your God did for you in Egypt before your eyes? Unto thee it was shewed, that thou mightest know that the Lord he is God there is none else beside him." (Deut. 4, 34-35)

Rosenzweig`s position is clear:

The presentness of the miracle of revelation is and remains its content, its historicity, however, is its ground and its warrant...Now it also finds the highest certain possibility for it, but only in this its historicity, its `positivity`. The certainty does not precede that bliss; it must, however, follow it. Experienced belief only comes to rest in this certainty of having been long ago summoned, by name, to belief (Star 215).

Elsewhere in his primary work, he wrote that "truth will forever be what it was whether from the a priori aspect or whether it is raised in the holy essence or earlier times" (Star 141). On the objective basis of viewing the past is the special means of observing reality determined. The accepted perception is derived from the assumption that the link between God and man is a pre-revelation; it is requisite to a perceived creation, in the accepted conception, as a willful act. Man passes from the monologue of the past to dialogue with God in the present. He passes from the knowledge that God is the creator and is present to the revelation that breathed life into this objective knowledge and made it the most vital, real and personal experience. There is an "opening of something locked" (Star 194, 195). And in the light of this revelation of love, "the souls can roam the world with eyes open and without dreaming. Now and forevermore it will remain in God's proximity. The `Thou art mine` which was said to it draws a protective circle about its steps. Now it knows: it need but stretch out its right and in order to fee God's right and coming to meet it" (Star 215).

Rosenzweig tells us that "there is a God" (Star 212,215). In developing the ideas of the German Protestant theologian Friedrich Daniel Ernst Schleiermacher (1768-1834), Rosenzweig asserted "there is something in consciousness which is above consciousness" (Naharayim 207). That is, "consciousness is the basis of realization, but there is also actuality in consciousness itself" (Naharayim 207). This actuality, according to Rosenzweig, is the irrational, metaphysical knowledge, which gives internal experience to belief. It frees one from the burden of determinism. Subsequent to Rosenzweig, Jaspers would speak of the certain refuge that belief grants, and Marcel and Buber of the "I and Thou" as an expression of relationship between man and God in prayer (see Einführung in die Philosophie). In the philosophy of each, man is certain.

Man can now be free in his creative acts, his desire and ability; he can create the reality, which is the subject of belief. Man cannot believe without an actual act. If, for example, Abraham had taken the intellectual, ethical path he would have disobeyed God since the intellect forbids human sacrifice. But Abraham was seized by the restraint of belief. He received his morals from his belief and not his intellect. This sensation demonstrated the objective certainty of faith, for which he is called the "mighty man of faith." Abraham teaches that what is impossible according to the calculations of men of morality and honesty is not only possible but is certain by means of the power of faith (compare Dialogical Philosophy 90-111). Abraham acted pursuant to the words of the prophet Amos 1:8: "He hath shewed thee, O man, what is good; and what doth the Lord require of thee, but to do justly, and to love mercy, and to walk humbly with thy God?" Such is the security, which grows from the experience of "walking humbly with thy God."

The soul needs irrational means to nourish its unconscious part. Man finds these irrational means in the rational and irrational revelation via the religious belief in his soul. The believer wants his creator to understand the foundations of belief; he wants to believe with intelligence and understanding and not only mechanically the commandments of God. The assumption of believing man is as expressed in Psalms: "An ignorant man does not know, and a fool will not understand this." The irrational is joined with conscious knowledge such that each requires the other and each is nourished b the other.

Rosenzweig tries to understand and know man by creating bridges with God and the world. And he succeeds in this task. He sees in man total humanity. Rosenzweig perceives perfect method in the world instead of the fragmentation, for example, which Jaspers found. Knowing God's love, man can now anticipate eternity to the present and, as a result, redeem the entire world. Man knows exactly from where the world came and to where it is going. He is not indifferent to the despair of the individual and the multitude. Man will not be lost in the world in the manner Kafka described nor will he be dislodged from his environment as dramatized by Sartre, nor will he be the tragic, heartless being of Heidegger. Instead, he will be immersed in love as he marches to the arms of eternity and the objective of the joy of life, happiness, security and fulfillment.

2. Rosenzweig perceives the fear of death as authentic, tragic reality, though he does not, like Heidegger, foresee in death and extreme, cruel, realistic termination which thwarts previous action.

In Rosenzweig`s opinion, death is something and not "nothing, " as Heidegger maintained ("Investigation" 22-24, 39-40). Death is the seed of life, the fetus that is born from the body of death. The soul died first and was resurrected in the arms of its lover.

Rather than being the end, death is the exclamation point of new life, life nourished, in fact, from the sense of death. Rosenzweig opened his book with a sentence about death and concluded it with the call "into life." He conquers death with the power of love because love is stronger than death. God's love removes man's loneliness and commands him to recompense with love. The beloved feels himself borne and protected by love. I am forced to live, but the single reason is not my death but rather my life, and not just life, but eternal life.

3. Man has purpose.

With the power of love directed from God, man loves his neighbor. He is liberated from the "you" in favor of the "we." The love of others is walking toward eternity, redemption of the world, the establishment of the kingdom of heaven. Eternity is the product of anticipation of the future in the present. The purpose of man is to march toward eternal life, to true bliss. With this purpose, man fulfills himself in all his essence.

Rosenzwieg tells us that "there is a God" (Star 212, 215) as it is said in Ps. 73, 23: "yet I was always with you, you held my right hand." (The words "I was always with you" are inscribed on Rosenzweig`s tombstone.) Man is certain that God will respond to the solitary soul, (Star 212) "for all His ways are judgment; a God of truth and without iniquity, just and right is He." (Deut. 32.4)

This certainty is the heart and soul of religion. It is the vital and true reality - the individual's awareness of God without requiring proof. Man creates the reality, which is the object of faith.

Man, with the internal power of belief, is at home in the temple of God, recognizing, knowing and loving Him. With his faith and knowledge of God, man also comes to know the world and, as a result, is able to redeem it. Knowing the love of God vanquishes death. Indeed, death is something, which creates a source to provoke new life. The existence of death strengthens love and ultimately redeems man and the world. The singular purpose of man's existence is not his death; instead it is his life, a life of eternity.

Rosenzweig paved for man a way of life, which protects man from the insufferable side effects of the fear of death. This is a path which brig man to his life's purpose – striding toward redemption and establishment of the kingdom of Heaven, obliterating the fearful sting of death along the way and concluding with the victory of life over death (The victory of life 46).

*) The life story of Franz Rosenzweig (1886-1929) has a strong link with his methodology. He grew up as an only child in an affluent, liberal Jewish home in Germany. In this home, he learned to love German secular culture. Although the members of his family recognized themselves as Jews, He did not receive a formal education in Judaism. When Rosenzweig matured, he studied medicine, history and philosophy at a secular university, but he did not find enough satisfaction in these disciplines. Instead, he looked to religion for fulfillment. Under the influence of several young Jewish friends who has converted to Christianity, He convinced himself that those who wanted to believe in God needed to be Christian. So Rosenzweig decided to convert as his friends had. This was during the summer of 1913. Before he left Judaism, however, he attended a small Berlin synagogue on Yom Kippur. While there, he witnessed such devotion and sentiment from the congregation that he no longer thought it necessary to leave his birthright. He turned back to Judaism. What he hoped to find in a Christian church, that strong spiritual belief, which sustains a human being, he found in this small, traditional synagogue. When he left this service, he was profoundly moved. He wrote his cousin "After prolonged, and I believe thorough, self-examination, I have reversed my decision . It no longer seems necessary to me, and therefore, being what I am, no longer possible. I will remain a Jew." He spent the next academic year reading Jewish texts and cultivating a close friendship with Hermann Cohen.

Yet, Franz Rosenzweig had to deal with one more spiritual conflict. And this time it was to lead to a philosophical revolution.

Rosenzweig was sent to the Balkan front to serve as an artilleryman with the German army during World War I. The young Rosenzweig, a patriot who loved his homeland, wanted to devote himself to it completely as a fighter, The young man, however, who has never suffered nor been impoverished suddenly found himself on the battlefield and meeting death every day. The war dared Rosenzweig personally, tested his ideals. Survival became paramount to him. He wanted to live, to come cack healthy and whole. In his eyes, life was his only possession. Yet all his developing, spiritual ideas did not seem clear and definite. He has just met Judaism. When he reached the front, under the fire of the enemy's gunners, Rosenzweig understood that all the things that he though were important were not. Earlier when he was a student of philosophy, he learned that only man's reasoning can raise him above death and above suffering; only it controls happiness and an orderly world. In the battlefield, however, Rosenzweig found it impossible to ignore the evil inherent in man, all the evil that brings wars such as the one he was fighting. While on the front, he started his masterpiece, The Star of Redemption, on army postcards and letters to his mother. Rosenzweig saw this work as his lifetime project. As an existentialist scholar, Rosenzweig tried to put the basic precepts of his theory into his everyday life such as the originator of existentialism, Kierkegaard, did. When he completed his work shortly after the war and saw it published in 1921, he maintained that what he had written was the basis upon which he would live, thereby implementing the basic precepts he discussed. Within a dew short years, Rosenzweing learned he had a disease, one which eventually paralyzed his whole body except for one finger. In spite of his disease, he held firmly to his existentialism. With aid from his family and a specially designed typewriter, he kept writing many essays and articles. Some of these articles provide the basis upon which Rosenzweig founded and established "The Free Jewish Studies House" in Frankfurt. In addition, hoping to five the Bible new spiritual depth, Rosenzweig translated the Bible into German with Martin Buber. He also translated an commented on the poems of Yehuda Haleve. He died at forty-three.

Rosenzweig`s life made him an existentialist and made him remain an existentialist. The experience of the war and then his illness compelled him to think in terms of survival. But not only that, these experiences continually kept the idea of survival ever-present for him. They forced him to question the meaning of life and death and how those concepts related to him as he live each moment of his life. When those life-threatening experiences were interpreted through his earlier return to Judaism, Rosenzweig established for himself a prominent place in modern Jewish thought by brining together Judaism and existentialism.

LIST OF SOURCE MATERIAL ABBREVIATIONS

Rotenstreich, Natan Al Hakiuym HaYehudi BaZman Hazeh [Jewish Existence in the Present Age]. Tel-Aviv: Kibbutz Artzi Publ., 1972

Al Hakiyum

Aquinas, Thomas. Basic Writings of Saint Thomas Aquinas. New york: Random, 1945

Basic Writings

Bergman, Samuel Hugo. Dialogical Philosophy from Kierkegaard to Buber. Jerusalem: Bialik Inst., 1974.

Dialogical Philosophy

Meinicke, Friedrich. Die Entstehung Der Historismus [The Becoming of History]. Munich: R. Oldenburg, 1936.

Die Entstehung

Hegel, George Wilhelm Friedrich. Enzyklopӓdie Der Philosophischen Wissenchaften Im Grundrisse [Encyclopedia of the Philosophical Sciences]. Hamburg: F. Meiner, 1959.

Enzyklopӓdie

Mendes-Flohr, Paul. "From Revelation to Religious Faith: The Testimony of Franz Rosenzweig`s Unpublished Diaries."Leo Baeck institute Yearbook. New York: Leo Baeck inst., 1970. 161-174.

"From Revelation"

Glatzer, Nahum N. Franz Rosenzweig: His Life and Thought. Philadelphia: Jewish Publ. Soc. Of Amer., 1953.

His Life

Sartre, Jean-Paul. L`Etre et le Niant [Being and Nothingness]. Paris: Gallimard, 1948.

L`Etre

-------. L`Existentialisme est un Humanisme [Existentialism and Humanism]. 2n ed. Jerusalem: Carmel, 1990.

L`Existentialisme

Helmholtz, Hermann Ludwig Ferdinand von. Popular Scientific Lectures. New York: Dover, 1962.

Lectures

Schwarcz, Moshe. MiMytos I`Hitgalut [From Myth to Revelation]. Tel-Aviv: HaKibbutz haMeuchad, 1978.

MiMytos

Rosenzweig, Franz. Naharayim [Selected Writings of Franz Rosenzweig]. Trans. Yehoshua Amir. Jerusalem: Bialik Ins., 1977.

Naharayim

Sartre, Jean-Paul. Portrait of the Anti-Semite. New York: Prtisan Rev., 1946.

Portrait

Kierkegaard, Seren. Post-Scriptum [Final Scientifique aux Miettes Philosophiques]. Trans. Paul Petit. Paris Gallimard, 1949.

Post Scriptum

Feuerbach, L.A. Principles of the Philosophy of the Future. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1966.

Principles of Philosophy

Rosenzweig, Franz. The Star of Redemption. 2d ed. Trans. William W. Hallo. New York: U of Notre Dame P. 1985.

Star

Dostoyevsky, Fyodor. The Brothers Karamazov. Vol. 2. Tel-Aviv: HaKibbutz HaMeuchad, 1965.

The Brothers Karamazov

Krouz, Zadok. The Victory of Life Over Death 3ded. New York: CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY P. 1996

The Victory of Life

Schopenhaure, Arthur. Die Welt als Will and Vorstellung. [The World as will and Idea]. Leipzig: Hesse & Becker, 1919.

The World

Zadok krouz was born in Jerusalem. He studied in various `yeshivoth` in Israel. He enlisted in the army, where he served in a combat engineering unit.

His academic career began at the Hebrew university of Jerusalem, where he obtained a master`s degree, `cum laude`.He has published books, various articles, a collection of writings on language and literature, religious existential meditation, philosophical doctrine of the human spirit and produced a number of self-hypnosis audio cassettes for improving the quality of life.

By:

3

With him will I speak mouth to mouth, even apparently, and not in dark speeches; and the similitude of the LORD shall he behold…

Numbers 13:8

Numbers 13:8

Abstract

The article will discuss place as dialogue between man and God. Man's place is in the middle of the universe as a living, real creation. Everything else surrounds him, including those people that he meets. This idea forces man to be within a specific time and place. Man's place refers to a specific time, the present, and a specific place, existence in the present. This makes man's place part of a dynamically moving stream of changing life-experiences, never stagnant and always flowing.

For this dynamic to occurs, man's place must be in a frame of dialogue that requires him to use the word "you," that is, the second persona singular pronoun used with a verb in the present tense. This pronoun forces man's communication to be immediate and present and quite interactive.

From this usage, a frame of dialogue develops naturally among three elements: God, man and the world. Together they create the All (Whole) through their dialogue with each other. Man's place, then, is in dialogue with God and the world.

Man’s place is midpoint in specific time and place.

In Rosenzweig’s philosophy, man’s place is at the center of the universe, as a real being. Man is not an object of the intellect1 which puts the world in order; rather, his is the center, the pivot around which everything turns: “Wherever it [a proper name] is, there is a midpoint…” (Star 218); “…on the seat of the kingdom of the world” (Naharayim 237). Natan Rotenstreich, in “The Philosophical Foundation of Franz Rosenzweig” (74-87), presents three points in support of this contention, which, in slightly expanded form, are as follows:

- The intellect voids the personal and individual existence of man; it makes the existence of man one variation of the inclusive unity. Rationally, there is no place for singularity, and therefore in this confrontation between the inclusive unity and individuality and, in particular, when speaking about the individuality of man, a centralized intellect cannot be assumed. When man is the object of the intellect, the subject is grasped by the object, such the self-consciousness is linked with the “I” as the form and content of perception. Everything is concentrated in the “I,” comprising a one-dimensional reality. The “I” is all’ consequently, the polarity of the elements God, man and the world is nullified. Polarity assumes that each of the three elements (God, man and the world), is complete in and of itself, each preserving its characteristics; the conception of “unity of the I” embraces all the elements within “I,” negating the singularity of the elements. Everything results from the I. The world, man and God are not independent elements outside the I. They are united in the total “all” of the “I.”

…the idea of reducing everything back to the self. The method of basing the experience of the world and of God on the experiencing self is still so much a commonplace of the contemporary philosopher that anyone who rejects this method and prefers instead to trace his experience of the world back to the world, and his experience of God to God is simply dismissed. This philosophy regards the reductive method as so self-evident that when it takes the trouble to sentence a heretic it is only because he has been guilty of the wrong variety of reduction. He is burned at the stake, either as a “rank materialist” who claimed that everything is world, or as an “ecstatic mystic” who claimed that everything is God. This philosophy never admits that perhaps someone might not want to say that everything “is” something else. (Naharayim 191)

This reality, the nullification of polarity, raises the surprising question: can there be self-immanence? (See, Introduction: Hegelian Theory and Reactions to it as Background to “The New Thinking,” p.7.) The serpent which eats its tail and consumes itself in its entirety, can this yet be called reality? (Naharayim 208) “…peel them as much as you want – you will never find anything but onion and not anything ‘totally other’” (Naharayim 223). The intellect as reality of one dimension only negates the self-existence of man insofar as he is man. The intellect lacks reality; it is immanence without external links and thus an immanence which proceeds nowhere.

Self-immanence is expressed in Hegel’s teaching that the real is the intellect and the intellect is real; nature, science and art are each a realization of reason. Individual man also is the materialization of reason, and only that which is reason exists.

Self-immanence is the Hegelian conception of the world via a consolidated and rigid view, a look replete with the ideal that science will never attain the infiniteness to the world nor can it bring man to concrete reality, to the recesses of his soul.

Self-immanence is the absolute spirit of complete reason and of abstract thought; it is not considered part of actual man who lives self-reliantly in the real world with his experiences and his real problems. Self-immanence encloses man in the world of abstract concepts and the infinite, and man does not know his life’s path. Hegel, by means of the supposition of immanence from man to man which commences with his reason, turns man into a segment of the theory, a portion of the cosmic world idea system. The world and man are one unit – they are “one flesh”.

Thus, due to self-immanence, man is comparable to a miniature world; he loses the connection to a real and vital actuality. It is not the self-immanence of reason which brings man to concrete and true consciousness; instead, it is the specific, fundamental experience of the existing elements themselves.

Rosenzweig defines thinking as follows: “…thinking” means thinking for no one else and speaking to no one else (and here, if you prefer, you may substitute “everyone” or the well-known “all the world” for “no one”) (Naharayim 200).

The inclusivity, or the unity of all, voids the connections, the links of the elements, and turns them into unity. Therefore, there is no connection to another. All human reality is swallowed up in unity, and the result is the absence of individuality, and of the futility of existence and ultimately the denial of death. [In opposition to this view, Rosenzweig considers the death and life of man to be the main point of the existential philosophy of man and not the “I” in the idealistic version, in which man serves as a point of reference for the problems of ethics, just as in science it is only the event.] Star of Redemption begins with the sentence “All cognition of the All originates in death, in the fear of death” and ends with the words “INTO LIFE.” The inclusive intellect denies and mocks the existence of fear, which is the essence of man in his surroundings. “…[I]n death…originates all cognition of the All…fear of death…roars Me! Me! Me!...Only the singular can die and everything mortal is solitary…death is not what is seems, not Nought, but a something from which there is no appeal, which is not to be done away with…And man’s terror as he trembles before this sting ever condemns the compassionate lie of philosophy’s cruel lying” (Star 45). The fear results from man’s reality—his being, encompassing the possibility of the end (“toward the end”). In his fear of death, man is made independent. Death is revealed as the special possibility of man as individual to be himself solely, without a trace of generality. Heidegger even reached the substantiality of death, which makes man live in his surroundings to the point that the living feed from death, since death is a possibility belonging to the reality of man.2

Rosenzweig attack on the method of the intellect can be summarized as follows: The intellect as that which brings order to the world is a poor alternative to the truth of multiplicity,3 an alternative which sees the essence of man as an adorned segment of the world or the Almighty, disguised, revealed in man as unity. And man becomes unity or the “All” rather than being an element, independent and authentic, unaltered, a theoretical, conceptual unity. “Philosophy was accused of an incapacity or, more exactly, of an inadequacy which it could not admit, since it could not recognize it” (Star 49). The intellect preferred understanding to man, since, for existential man, “speaking means speaking to some one and thinking for some one. And this some one is always a quite definite some one, one who has not merely ears, like “all the world,” but also a mouth” (Naharayim 231).

- Historically, the intellect has an anti-religious or anti-theological tendency, because the intellect has given understanding precedence to the data understood by it. Therefore, it prefers understanding to fundamental data, including the fact of the existence of God. Can it be that the “I” creates the world within it? A world not dependent on a transcendental being contradicts the religious faith in the act of creation, which depends upon a transcendental being (Naharayim 225-6).

- The intellect tends toward unity and monism. It prefers the homogonous to the heterogeneous. This tendency creates a false impression of a unified world; whereas, by its nature, the world is not unified. The intellect summarizes the belief that there is one source for all the natural – both material and spiritual – phenomena, that all of reality is explained by one principle alone (Naharayim 223).

These three points loosely summarize the basic reasons Rosenzweig did not adhere to the intellectual approach: that man is the object of the intellect which sets the world in order. The place of man, according to Rosenzweig, is in the center of the active universe as an actual being. Rosenzweig holds that man, as the center, orders the external world pursuant to his experience, and which experience enables man to see light (Naharayim 223; Star 218). The experience enlightens everything, whereas an objective matter is distant and receding. His entire vision is founded on the subjectivity of the human experience, and from this view—and only from it—is revealed “everything” in the communicative network. Man is the lord of creation,4 according to Rosenzweig, “in the chair of the kingdom of the world” (Naharayim 237).

Yet, with all the singularity of Rosenzweig’s personality and teaching, his philosophy is neither singular nor unusual. It is a part of a more inclusive spiritual movement, whose beginnings were inherent in the period of post-Hegelian thought in Germany. The core of such thought was not longer the abstract method, nor the concept in its independent movement, but rather actual man, vital man, fettered with his existential problems.

…to know God-man-world means to know what they do or what is done to them in these times of substantiality – do this to this and is done to this by this (Naharayim 230)…[the approach of “the New Thinking”] knows only what experience attempts – but this it knows concretely, without paying heed to philosophy which denounces it as knowledge beyond any possible experience. (Naharayim 240)5

Rosenzweig writes that “the goal of our philosophy is not to be philosophers but people, and, therefore, we must give to our philosophy a dimension of our humanity” (Briefe 718). The human, living, real existence is the action center of the entire structure whereby the actual human existence, the entirety in its reality, is given to man by actual revelation; the theological turning point becomes clear from the central position of the human being also in theology. Living man, as a real individual being with his real existential problems, anguished in body and soul, has forever been the subject of theology. Philosophy and theology each deal with the center of the life of man. “As opposed to the Copernican revolution of Copernicus…the Copernican change of Kant compensates him by seating man on the chair of the kingdom of heaven in a much more real manner that Kant himself thought” (Naharayim 237).

This is the focus of Rosenzweig’s philosophy, which commences and terminates in individual man. The man about whom he writes is a real, everyday man, not the abstract man who is the subject of many philosophical theories. Possibly Rosenzweig was influenced, inter alia, by the Biblical story, for within the story of creation of the world stands precisely the story of the creation of individual man. Clearly, the story of the creation aspires and leads to Day Six, to the description of the creation of man, for that is the main object. Our Sages expressed this in their commentaries and even graphically (Bereshit Raba I). Why, it was asked, was the world created with the Hebrew letter Beth? The response was that Beth is closed on three sides. That is, you, man, do not look behind or to the sides, but in front of you to see the path you are taking. This is the purpose: to see where you are going and not to demand the more wondrous than you. When the Hebrew letter Aleph attacked, asking why the world was not created with it, it was told that the Ten Commandments begin with Aleph, and the entire world was created only for the Ten Commandments. That is, guidelines for the way one should live. They are commandments to man located in the center. “Wherever it is, there is a midpoint… For it demands a midpoint in the world for the midpoint, a beginning for the beginning of its own experience” (Star 218). This also appears in Ps. 8:6, which completes the story of Creation: “for thou hast made him a little lower than the angels and thou crownest him with glory and honor.” Man is the midpoint of the world, demanding the midpoint in the world and being “seated on the chair of the kingdom of the world” (Naharayim 237).

Everything else surrounds man, including the other with whom he meets. A meeting or conversation between two beings is a fulfillment of one of a multitude of possibilities available to man. This anthropocentric idea requires man to be at a specific time and place, for his individuality cannot be forever without time and place:

…[The I or the Thou] is its own category....Rather it carries its here and now with it. Wherever it is, there is a midpoint and wherever it opens its mouth, there is a beginning.... In keeping with its creation as man and at the same time as ‘Adam,’ the ‘I’ is the midpoint and beginning within itself. For it demands a midpoint in the world for the midpoint, a beginning for the beginning of its own experience....Thus both the midpoint and the beginning in the world must be provided to experience by this grounding, the midpoint in space, the beginning in time.... The ground of revelation is midpoint and beginning in one. (Star 218-19)